Family History

Website link to Fortescue Family

The Lunan Family

By Duncan Lunan

‘Lunan’ is an old Scottish place name, best known from Lunan Bay, Lunan River and the district of Blacklunans, all in Aberdeenshire. Lunan Bay near Montrose is 5 km from the main A92 road to Aberdeen and has a 5 km crescent beach, best seen from Boddin Farm, 3 km south of Montrose and 3 km from the A92. But I haven’t been able to trace any Lunans from there, still less ours.

Other Lunan Families

There are three Scottish families that I know of called ‘Lunan’, with no relationships between them. Our branch takes its name from ‘the lands of Lunane’ in Aberdeen, and the family of Dr. Charles Burnett Lunan at the Western Infirmary, including the Rev. David Lunan, (three times Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, with whom I’m often confused), hail originally from a tiny village of Lunan on ‘the Lunan burn’ outside Blairgowrie.1 I have their family tree back to 1800, and ours back to 1600; there’s no overlap of the trees or commonality of Christian names between them or with another Lunan family in England, who can only trace back a couple of generations. Curiously, nor are there any connections with Lunan Bay or the other Lunan placenames.2 They could of course be descended from one of the other branches of the family on the upper levels of the tree, but without commonality of Christian names or placenames there’s no indication of it.

There’s also Mike Lunan (Michael John) of Kircaldy, Arran and now Caithness, born 1942, whose grandfather was John Lunan of Alyth in Fife (d. late 1960s), one of a large family but not of ours; he and the Rev. David Lunan have a common set of great-great-grandparents, making them third cousins, the common ancestors being John Lunan 1812-1902 and Janet Gellatly 1811-1892, not members of our family tree.

Mike’s grandfather John Lunan was born in Alyth in 1881; one of several children of James Lunan (1845-1912) and Helen Howie (1848-1932). The latter James Lunan was one of 6 children of John Lunan and Janet Gellatly. This John and his brother both married sisters (perhaps twins) called Gellatly. These brothers were the sons of John Lunan b.1779 and Margery Ogilvie b.1786.

There’s also a Charles Lunan, a clockmaker in Aberdeen who made ‘mathematical and other instruments’ with a James Dalziel in the early 19th century, followed by a William Lunan, watchmaker of Aberdeen, whose ‘frictional electrical machine’, built between 1824 and 1833, is preserved in the National Museum of Edinburgh. But there’s no Charles in our family tree in that time-frame. Charles’s obituary reads:

LUNAN, CHARLES, sen. Aberdeen, 1760-1816.

Died at Aberdeen on the l0th January 1816, Mr Charles Lunan, clock and watch maker. He was a man of uncommon shrewdness, intelligence, and native strength of mind, and from his inventive genius in mechanics much might have been expected had his powers received a more early culture, a circumstance which he often regretted during the latter part of his life. He has, however, left behind him many specimens of his ingenuity and of the accuracy with which he could execute the finest pieces of mechanism." Edinburgh Evening Courant, 20th January 1816.

"Ann Aiken or Hewit, served Co-heir of Provision General to her grand father and mother, Charles Lunan, watchmaker, and Mary Thomson, spouse, Aberdeen, dated 8th March 1855. Recorded 19th March 1855." (Services of Heirs.)

In compiling the Lunan family tree, I was concentrating on the Lunans from whom we're directly descended, in which line the dominant boys' names throughout are Alexander, John and George. In the big 18th century family (see below), there are younger sons called William and James, but no Charles, so there's no definite link to Charles Lunan, the instrument maker of Aberdeen. He might have been the son of the 18th century William or James, whose children wouldn't have been found by my uncle's 1930 researcher if they had moved outside the target search area of parish records. But it's possible that their family might simply have taken their name from what was then 'Lunan's Quarter' in Aberdeen, as the 14th century descendants of the illegitimate Alexander did when they lived there, and not be related to us at all.

There are one or two other possible connections, e.g. the last three Lunans listed on United States websites in the 1970s are all descended from a 'farmer Lunan' who emigrated from Scotland to Canada, then moved south, who may be 'one of ours' (see below). I asked the late Larry Niven why he and Jerry Pournelle had named a character 'Lunan' in their novel Oath of Fealty, and he gazed into the middle distance (easy to do, with his thick glasses), and he said, "Oh, we thought it was a good name - and he's not an unsympathetic character..." There's also a director of a private educational observatory in Australia, who's descended from a Lunan who just might be the ancestor of mine who deserted his family and ran away there. Given what I do for a living, it’s funny how the possible outlying branches of the family seem to have been pushed in similar directions.

Our Lunan Family

In 1930 my late uncle Gordon Lunan put his watch in for repair in Edinburgh. When he went back the shopkeeper assured him, “There will be no charge, sir.” “That’s very strange,” said my uncle, “why should that be?” The shopkeeper replied, “I make a study of the derivations of names, and you, sir, are descended from the astronomers of ancient Chaldea. That means, sir, that your ancestors invented the calendar, so making agriculture possible and so making civilisation possible, and to charge you for the repair of a timepiece would be an effrontery.”

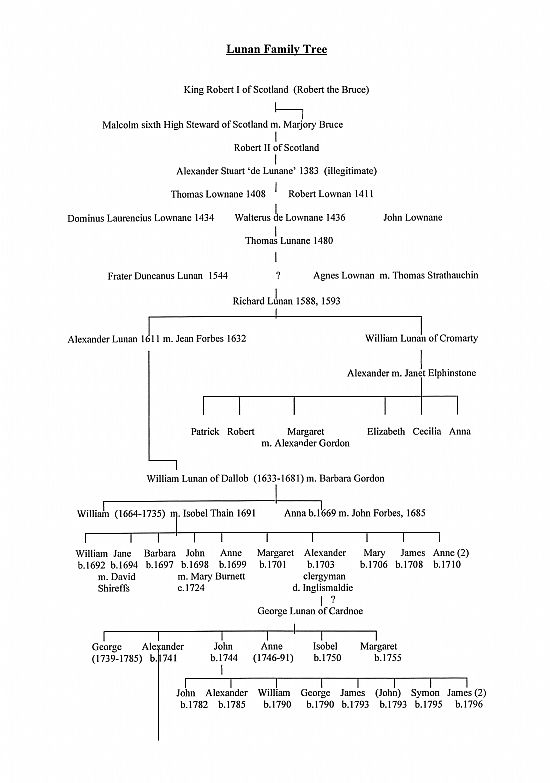

My uncle was so taken with that that he set about writing to older family members for information, and commissioned a researcher to investigate in the National Library of Scotland and in the parish records of Aberdeenshire. She was able to find a lot of information but not to make sense of it. Eventually the material was passed to me and with the help of my first wife Linda, we repeatedly modelled the family tree until we had a model which fitted together without contradicting any of the known facts. One indication that we succeeded is that Gordon was told by his great-aunt, Jane McKeggie, that in the eighteenth century his great-great-grandfather, possibly named George, had a family with thirteen children, farming at Broomhead, Fraserburgh. We found two brothers, Alexander and John, whose father and elder brother were both called George. Alexander and John farmed together and were godfathers to each other’s children, fifteen between them, two of whom evidently died in childhood. Since two of the sons were born in 1793 to the same father, but christened separately, the implication is that one of them was illegitimate – probably John, who’s shown in brackets in the family tree for that reason, because there was a legitimate son of the same name.

However, in 1981 I exchanged letters with Mrs. Nancy Lunan of Edinburgh, widow of James Douglas Lunan, who was the son of George Lunan. George and James ran chemists’ shops in Edinburgh. She said George Lunan’s father had a farm called Broomhill outside Fraserburgh and had seven children, she thought. Since James and George are both common Christian names in our side of the family, her husband’s grandfather could have been George, the elder brother of Alexander and John.

Uncle Gordon had also tried without success to find the meaning of the name. We pushed the background research further – a lot further - and it turned out that the old watch repairer in Edinburgh knew what he was talking about, although he was wrong about direct line of descent. In “The Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology” there is a statue of the high priest of one of the tributary cities of Ur, in Chaldea, making an offering to the Moon-god.3 The Moon-god’s name was Nanna, and the priest’s was Lu-Nanna, ‘Moonlight’. The combined word became the Indo-European root word for the Moon and appears in Latin as ‘Luna’, in French as ‘La Lune’, and in Celtic and Gaelic tongues as ‘Lugh’ (Welsh Lleuw), the Moon-god, picking up the wrong syllable from the original! In England he became ‘Lud’ and gave his name to London, (‘Lud’s Town’), and ‘Ludgate’. But in Gaelic the ‘n’ part of ‘Luna’ was preserved in Lugnasagh, the Celtic harvest festival,4 and that probably explains how it became a place name, e.g. ‘the field of the harvest festival’.

Until recently, after describing my family background I’ve gone on to say that my late mother could regard the Lunans as Johnnies-come-lately, because of her own Fortescue background (see ‘Recent Generations’, below). However I’ve purchased a scroll of the Scottish and English royal family trees, produced at Paisley Abbey and sold at Dundonald Castle, which was built in its present form by Robert II of Scotland in the 14th century. Robert II was the grandson of Robert I (‘The Bruce’), and on it we Lunans have three lines of descent: from Fergus I, King of the Scots in 500 BC; from Egbert, King of Wessex in 802-839 AD, via Alfred the Great, Ethelred the Unready, Edmund Ironside and his granddaughter Saint Margaret, who married Malcolm Canmore of Scots, and on down to Robert the Bruce. The third line is from Alan, Dapifer or Steward of Dol in Brittany, through Walter FitzAlan, First High Steward of Scotland (reigned 1160-1178), down to Walter Stewart, who married Marjory Bruce, and their son Robert II (reigned 1371-1390) – which brings us to the Lunans.

In 1383 Alexander Stuart, an illegitimate son of Robert II, bought ‘the lands of Lownan [or Lunane] and Pitfour’, probably a French form of Lugnasagh, from Ricardus Mowat, successively chaplain, canon and chancellor of Brechin Cathedral.5 Robert II had many sons, both legitimate and not, and it was his practise to stabilise his kingdom by settling them in outlying parts in sufficient comfort that they weren’t disaffected through having too little, tempted to risk the consequences of rebellion to gain more, nor having so much that rebellion might gain them it all.6

Alexander followed Mowat in styling himself ‘de Lunane’ and because he was illegitimate he or his sons seem to have made it a formal surname. The court beside his house, between the Gallowgate and the Loch, was known as ‘Lunan’s Court’ until the mid-19th century. He became a councillor of Aberdeen in 1398, Robert Lownan was admitted as a burgess in 1411, and Dominus Laurencius Lownane was there in 1434. In 1435 he built a new school in Dundee, ‘without leave from the bishop’, for which he was rebuked. Thomas Lownane was in Aberdeen in 1408. Walterus de Lownane was a Notary Public and canon of Dunkeld in 1436, and was given safe conduct into England as Clerk of Scotland in 1439, while John Lownane was a canon of Brechin and owned property in the Apilgate of Arbroath. In 1480 Thomas Lunane owned property in Mongallie, as did William Lunan in 1643 (see below). In 1544 Agnes Lownan was the wife of Thomas Strathauchin of Aberdeen, and the same year Frater Duncanus Lunan [!] was a member of the Conventus of Deir. In 1588 Richard Lunan graduated from Edinburgh University, and became minister of Marykirk in 1593.

His son Alexander Lunan went to King’s College, Aberdeen in 1611, graduated M.A. with Honours in 1615, became Humanist in the University in 1618 and Regent in 1626, when he was parson of Monymusk, later minister of Kintore. Alexander’s brother William graduated M.A. from King’s College in 1626, becoming servitor to Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty by November 1638. He seems to have been a colourful character, because in February 1645 the Presbytery of Turiff was appointed by the General Assembly ‘to proceed with his excommunication’. Nevertheless he was admitted to the Presbytery of Garioch by October 1666, and was still minister there is October 1671.7 Alexander’s son William Lunan of Dallob (1633-1681) was also a Notary Public and minister of Daviot 1663-77. He had two children, William and Anna. This third William was born at Dallob in 1664 and married Isobel Thain, by whom he had ten children.5,8 His cousin Alexander, son of William of Cromarty, graduated M.A. from King’s College in July 1664.9

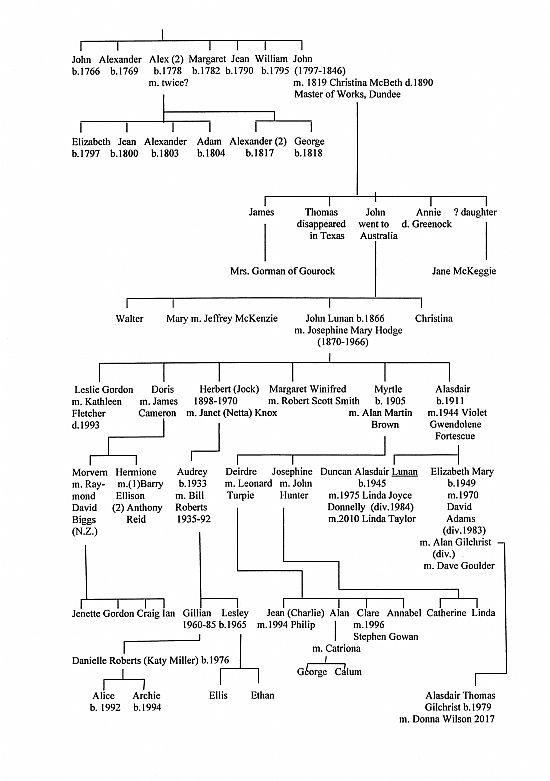

By 1700 the Lunans were well established, principally as Protestant chaplains to the Cadenhead family. Alexander, son of William of Cromarty, was deported to America in October 1716 for having been ‘out’ with the Old Pretender. Alexander and George remained the two most prestigious family Christian names. As time went on the Lunans intermarried with the Cadenheads and their close relatives the Shireffs, with the result that in the 1720’s the Cadenhead history says the family name died out with a son named Alexander, a country minister. Just at that time, however, a ‘George Lunan of Cardnoe’ appears in the same area as a tenant farmer, calling his children and grandchildren George, Alexander, John, Anne, Isobel and Margaret, just as the more prosperous Lunans of the previous century had done. The family continued as poor tenant farmers into the 19th century, with several emigrating to the USA and Australia, before John Lunan (born 1797) broke new ground in becoming Master of Works of Dundee. One of the emigrants was probably the farmer Alexander Lunan who went to Canada c.1830 with his son and then to the USA, founding the American Lunan family, whose grandchildren Spencer Lunan, Kenneth Lunan and Helyn Lunan Pinkoz (née Helyn Tifford Lunan) contacted me in the 1970’s. The Canadian Lunans, who visited us in Troon a few years earlier, had traced their ancestry to the Blairgowrie family to whom we are not related.

The Hodge Connection

My grandfather, John Lunan, born in 1866, was a buyer of ladies’ gowns for Arthur & Co. on Queen Street, Glasgow. He married Josephine Mary Hodge (1870-1966), a schoolteacher. They met in the Trossachs, where her family had a holiday home. Her father had sailed round the world before the mast (three times, I was told as a boy), and afterwards was an excise officer in Stornoway, with his own yacht and piper. He also worked in King’s Lynn and other places. The family moved to Aberdeenshire and then to London, but seem to have been unlucky and to have “buried a child everywhere they went”. There doesn’t seem to be a record of my maternal great-grandfather’s Christian name; nor of his wife’s, though she came from Bo’Ness, and her surname was Duncan, from which comes my first name. Apparently she had red hair, was married twice, and had a brother named Tom. There was also apparently a connection with Sir James Fergusson (not the Ayrshire family), whose daughters were artists. In the next generation Albert Hodge’s first exhibit at the Royal Academy was a ‘Bust of A.V. Hodge’, 1900, but that could have been his elder brother, not necessarily his father.

I was told that Josephine had fifteen or sixteen siblings, including three sets of twins; another version says nine or ten, but I have the names of only six. Alec, the eldest, survived the Boer War and after his return made his living as a distiller. One version says Josephine was the second child, and Mabel came sixth. Elsewhere in the sequence came Albert, born on Islay in 1875, who was six years younger than Josephine; and Rory, an analytical chemist, who might have been older because he married Albert’s nurse – depending on whether Albert was then little or grown up! There was also Ginny, and another version makes her older than Josephine, Rory and Sandy (Alexander). Albert was a keen fisher and golfer, and he and Ginny liked to fish the River Stincher.

Albert’s death in 1918 at the age of 42 put an end to an extremely promising career as an influential member of the ‘Glasgow Boys’, a sculptor and architect who won a gold medal, a silver and four bronzes at Glasgow School of Art, and took first prize in the UK Architectural Design Examination.10 He then continued training in the offices of Mr. Lieper of Glasgow in the 1890’s, and in 1901 he was commissioned to create the winged figure of ‘Light’ on top of the pavilion, among other sculptures for the Empire Exhibition in Glasgow. Albert exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy. One of the family treasures was a bronze statuette of a cherub playing with a frog, sitting on the head of an old man whom he has apparently just shot through the throat – one of a series of macabre combinations of childhood and death which Albert sculpted and exhibited at the R.A..11 This one is special because the model for the cherub’s head, at 3 years old, was my late uncle Leslie Gordon Lunan, who started the enquiry into the family history back in 1930. In his thirties Albert married Jessie Dunlop, daughter of Hamilton Dunlop, who ran puffers to Campbeltown and left an inheritance to Albert’s son Norman, who suffered badly from asthma and eczema; so did I as a child, but there may be no family connection, because my problems seem to have been due to an undiagnosed allergy.

In 1899-1900 Albert sculpted the figures on the Anderston Savings Bank, near where I lived from 1995 to 2012. Other figures include groups on the Caledonian Chambers of the Caledonian Railway Company in 1901-03, on Welbeck Abbey, the town halls of Cardiff, Glamorgan, Hull and Deptford, and (1908) on the Clyde Navigational Trust Building, later the Clyde Port Authority and now Clydeport HQ, at 16 Robertson Street; three cherubs in Glasgow Cathedral, and on the Pettigrew & Stephens building in Glasgow; the coat of arms on the National Bank Buildings on St. Vincent Street, figures on the Mail office in Union Street, a sculpture on the Manchester House in Sauchiehall Street, and a series of panels representing arts and crafts in the Grosvenor Ballroom;10-12 as well as (possibly) wood carvings at 22 Park Circus. He also created a statue of Queen Victoria at the Victoria Infirmary, and a figure of Mercury for the town hall in Clydebank. He has figures on Welbeck Abbey, the town halls of Cardiff, Glamorgan, Hull and Deptford, and was the major sculptor for the Manitoba Legislative Building in Winnipeg, Manitoba.13

Our closest family connection is with the statue of Robert Burns, with four plaques on the base featuring scenes from the poems, which stands on Dumbarton Road near Stirling Castle, unveiled in September 1914.13 The scenes were originally carved in plaster, from which the moulds were taken, from which the bronze plaques were struck. The statue was unveiled in September 1914;14 I inherited the originals of two of the plaques, featuring ‘The Cottar’s Saturday Night’, and the poet himself with his muse in 'To Mary in Heaven', which addresses Venus in the morning sky as ‘Thou Lingering Star’. The ‘Lingering Star’ plaque and the statue of Burns were both based on one of the few portraits of Burns during his life, showing him to be a lot more handsome than he’s usually portrayed. Cold-cast reproductions of the plaques by Dalserf Heritage, commissioned by Cyrus Laurie in 1983, used to hang in Laurie’s Bar on King Street in Glasgow. The originals were acquired by Elspeth King for Smith’s Museum in Stirling, restored by the artist Colin McQueen, and now hang in the meeting room (used by the Stirling Astronomical Society), which also holds drawings by Alasdair Gray. The original of the third plaque, illustrating ‘Tam O’Shanter’ with Hodge’s signature, is in the Tam O’Shanter bar in Ayr, where it was rescued from a skip when the pub took over the site of a former museum in 1993. The whereabouts of the fourth, ‘To a Daisy’, are unknown.

Albert also carved plaques for the Wallace Monument in Elderslie, William Wallace’s birthplace, which was not completed at the time, and was confused in our family with Bruce’s Stone, erected in 1929 to commemorate the minor battle of Glen Trool, actually fought in 1307 by our ancestor, Robert the Bruce, before his more decisive victory at Loudon Hill.. The plaster panels for the Wallace Monument were preserved in Paisley Museum and after more than fifty years Wendy Wood of the Scottish National Party started a fund to have the plaques cast, at the urging of Albert’s daughter Peggy.15 She had inherited her father’s talent and created the lettering for the tomb of Lord Kitchener. In 1970 they were installed by the Clan Wallace society on the monument at Elderslie.

In London Hodge’s works include sculptures on the former Port of London Authority building at 10 Trinity Square, London, a giant statue of “Neptune” and figure groups representing “Produce” and “Exportation”. These figures, although sculpted at the early stages by Hodge, were finished off by Charles Doman, between 1912 and 1922, working from Hodge’s sketches and drawings. Doman was Hodge’s assistant over many years. Hodge also created the allegorical figures for No. 4 Millbank, London (at the corner of Great Porter Street), and also the putti and coat of arms in Great George Street, London, over the main entrance of the Institute of Civil Engineers. Hodge also completed the figures of Wedgwood and Chippendale on the Victoria and Albert Museum façade.

Late in his life Albert won the competition for a national monument to Captain Scott and his party, although the project was delayed by the First World War and Albert died before completing it. The memorial, 37 feet in height, has allegorical figures representing “Courage”, supported by “Devotion” and crowned by “Immortality”. “Fear”, “Death” and “Despair” are trampled under foot. The bronze medallions hold portraits of Scott and his fellow explorers, Oates, Wilson, Bowers and Evans. The family thought this group sculpture was on the Thames, on the Embankment; my late Aunt Myrtle believed it was in Portsmouth Naval Dockyard, but I’ve visited that one and it’s a rough single figure, not a patch on Hodge’s detailed work. A statue in Waterloo Place, off Pall Mall in London, is also a single figure.

However I have now traced the Hodge sculpture and it’s located at Mount Wise, Devonport, Plymouth, erected in August 1925. It was commissioned by the Mansion House Committee of the Captain Scott Fund, which had also financed the memorial tablet in St. Paul’s Cathedral, at a total cost of £18,000, with the balance going to an endowment fund in aid of future Polar research. The intention was to erect the Scott Memorial statue in Hyde Park, in front of Lowther Lodge (home of the Royal Geographical Society), but no suitable spot could be found. The sculpture was completed by Albert’s brother Roderick and Mr. Doman, overseen by Sir Thomas Brock at Roderick’s suggestion. The Scott memorial was unveiled on Monday August 10th 1925 by the Commodore of the Royal Naval Barracks, C W R Royds, who had accompanied Scott on a previous expedition before Scott’s death in 1912.

Recent Generations

My father, Alasdair Lunan, was the youngest of a large family living at Westwood, 5 Albany Drive, Rutherglen, outside Glasgow. My grandfather, John Lunan, insisted that this last child be called Alexander, but my grandmother, who disliked the name, had him christened with the Gaelic translation ‘Alasdair’. That is my middle name and my nephew’s, so the family tradition is in a sense still going, but ‘Alexander’ is up for grabs. However it will soon go, because I am the only male Lunan in this generation and I have no children.

The oldest brother was Leslie Gordon Lunan, an artist and architect who married Katherine Fletcher, and rose to prominence as the equivalent of a bishop in the Christian Science movement. Alasdair’s eldest sister Doris married James Cameron, a buyer for Fry’s Chocolates, at the Grand Hotel in Glasgow, moving to Surbiton; their daughters, Morvern and Hermione, went to New Zealand. Herbert John (‘Jock’), next younger, was a traveller in shirts for Strachan, Crerar and Jones, men’s outfitters; he married Netta Knox, and their daughter Audrey married Bill Roberts, an engineer with Rolls-Royce at the National Engineering Laboratory in East Kilbride. Margaret Winifred, a solicitor, married Robert Scott Smith, a solicitor in Rutherglen; and Myrtle, a schoolteacher, married Alan Brown, who was Company Secretary of the Ailsa Shipyard in Troon. They lived in Wales, in Prestwick and lastly in Troon, at 7 Polo Gardens. Their daughters, Deirdre and Josephine, married Leonard Turpie and John Hunter, respectively. Leonard and Deirdre had distinguished careers as a Councillor and as a solicitor, Sadly they both died relatively young, but not before their four children were grown.

Aunt Myrtle told me that my grandfather offered Alasdair the chance to go to university but he had no academic interests, wanting only to be a professional golfer but lacking the independent means which were necessary for that career in those days. He was also good at football and had a trial to play for Queen’s Park. Dad later said that his father had been made redundant and couldn’t afford to send him to University, which was what I’d first heard. He would have studied English, History and Languages had he been able to; instead he went to work for Scottish Oils and Shell-Mex, first as a trainee and then as a tanker driver. That was a reserved occupation at the outbreak of the war but on 1st July 1940 he was released and joined the Cameronians, the Scottish Rifles, at Maryhill Barracks. He became a corporal, played golf for the battalion and trained in the Signal Corps, then in mountain warfare at Bridge of Allan. In 1941 he took a draft to Algiers, was commissioned into the 51st Highland Division, 9th Seaforth Highlanders, becoming a lieutenant and later a captain; he fought with the 4th and 6th East Surreys in North Africa, before sailing from Bizerta to Salerno, taking part in the Salerno landing and subsequent “officers’ mutiny”, after which he was attached to the Sherwood Foresters 46th Division, in the 5th Army under General Marc Clark, and stayed with them until shortly before the assault on Monte Cassino. In 1943 Clark allowed ‘Jocks’ to rejoin the Seaforths and he served in Catania with the 2nd Battalion in Sicily, transferring almost immediately to the 5th ‘Wildcats’ Battalion, with whom he returned to train for D-Day with the 9th Seaforths at Much Haddam in Hertfordshire, during which he met my mother at Hunsdon in October 1943.

Violet Gwendolene Fortescue, known as ‘Virginia’ and as subsequently as ‘Gwen’, was a member of the Fortescue family. Robert le Fort was charged by Charles le Chauve to defend the Loire and Seine region, and his son defended Paris against the Normans in 885, being elected king in 888, succeeded by his brother Robert in 923.8 Baron Richard de Fort was one of William the Conqueror’s guard of shieldbearers at the Battle of Hastings and, having saved the king’s life and been well rewarded, he adopted the motto forte scutum, ‘a strong shield’, which became a distinguished English surname. My cousin Jill Bowyer has researched the history of our branch of the Fortescues, and at one stage we were pearl-fishers on the River Colne in Essex.

Sydney Fortescue, my grandfather, was a Director of public companies in the City of London. Gwen took a diploma in French and German in Switzerland and spent some time with my uncles in Burma before the war. She joined the WAAF in 1940 against my grandfather’s wishes, and was a plotter at RAF Hornchurch before transferring to admin duties in 1941, later to Codes and Ciphers, later becoming Senior WAAF Officer, the ‘Queen Bee’ at RAF Hunsdon, one of the larger fighter and fighter-bomber bases,16 where she met my father in 1943. He went in on D-Day and was wounded soon afterwards, shot three times. There have been conflicting accounts about what happened, one that he was shot from under a white flag by a machine-gunner whom he then killed with a grenade, the other (the only time he talked about it himself, late in life, when we applied for compensation for his injuries) was that he was shot with a machine-pistol after calling on a German to surrender, and it was a comrade called George Lyle who ‘finished him off’. He was evacuated by his CO and the padre, on a mill door carried by a Churchill flame-thrower carrier, which was shelled as they withdrew, and he was sent back to England on an amphibious DUKW which broke down in the Channel and drifted for two days.

John Lunan died while Alasdair was in France and is buried in Rutherglen Cemetery.

My parents married in December 1944 at Hersham, Dad and the best man staying with Doris in Surbiton the night before, and my cousin Shirley (daughter of Mum’s older sister Gladys) was bridesmaid. I was born in October 1945 in the Elsie Inglis Nursing Home in Edinburgh. Before my father left the Army he rejoined the 9th Seaforths at Dumfries Castle, where we were billeted at Hoddam and also lived in Lockerbie (so I was told, though there’s some doubt about it), before Dad was demobbed in January or February 1947 at Redford Barracks in Edinburgh. When he rejoined Shell we lived in Hyndland, Partickhill, Glasgow during the hard winter that year, and then at Croftfoot, when he was a Superintendant at Kilmarnock, but he soon accepted a transfer to the Ayr office for the sake of golf, because Old Troon, now Royal Troon, was offering complimentary memberships to ex-servicemen. For a time he was a committee member and eventually had a complimentary Life Membership. He was also a keen dry-fly fisher for trout and salmon.

At first we lived in Woodfield Road, Newton-on-Ayr, where my sister Mary was born at home in April 1949. Soon after we moved to 26 Victoria Drive, Troon, then to 10 Darley Crescent, and next to a house of our own at 73 Bentinck Drive. Mary and I went to Primary School in Academy Street, then Barassie Street, then to Marr College. I went on to Glasgow University in 1963 and graduated in 1968 with an Honours M.A. (2nd) in English and Philosophy, with Physics, Astronomy and French as supporting subjects. Meanwhile the family moved back to Darley Crescent at no.16. The general degree made me almost unemployable so I’ve been self-employed as an author, lecturer, tutor, researcher etc for most of my adult life, except for four spells: I was a management trainee and researcher for Christian Salvesen (Managers) Ltd., 1969-70, Manager of the Glasgow Parks Astronomy Project, 1978-79, Photo-Archivist for the Glasgow 1990 Press Centre, European City of Culture, 1990-91, and Manager of the North Lanarkshire Astronomy Project 2006-2009. In 1983-84 I unsuccessfully attempted teacher training, but I gained a postgraduate Diploma in Education from Glasgow University with Merit and Exemption.

Mary worked as a telephonist for the Post Office and BBC Television Centre, London, and later as Practice Manager for a group of doctors in Hamilton, Lanarkshire. In 1970 Mary married David Adams of Stewarton, later moving to the Troon Harbour area, and in 1975 I married Linda Joyce Donnelly and moved to Irvine. My parents then moved to Braefoot Cottage, Eliock, Dumfriesshire, where they stayed until 2001. Mary divorced David and next married Alan Gilchrist, and had a son, Alasdair Thomas, born in 1979, living in Birmingham, Redditch, Edinburgh, Wishaw, Hamilton, and now Bonar Bridge, where he married Donna Wilson and they live with her daughter, Nadine.

My first marriage failed in 1982. From 1983 to 2012 I lived in Glasgow, and meanwhile Mary married our old friend Dave Goulder, of Rosehall in Sutherland. In 2001 my parents moved to sheltered housing near Mary, in Ardgay, at the head of the Dornoch Firth, and from there into residential care at Edderton outside Tain, where my father died in 2004. My mother went to live with Mary and Dave at Rosehall, then to full residential care at the Oversteps Home in Dornoch, where she died in late October 2016, just short of her 103rd birthday.

Meanwhile I married Linda Taylor in 2010 and moved back to Troon in 2012. In 2017 and in 2019 we attempted to move to southern Ireland, because Linda is still an Irish citizen, but neither attempt was successful and we returned first to Prestwick, then Ayr, back to our previous flat in Troon, and finally to Lamlash on the Island of Arran in March 2024

References

1. “Before I go on, let me explain that the Gothans was a place three miles outside Blairgowrie on the Perth road which was the campsite favoured by the traveller folks before the last war. The Lunan burn flowed past the site on its way to join the river Isla, and featured a perfect deep pool for dooking. As a matter of fact, ask most of the travellers in Perthshire wher they learned to swim, and they’ll tell you the Gothans.” Jess Smith, “Jessie’s Journey, Autobiography of a Traveller Girl”, Mercat Press, 2002.

2. A.H. Miller, “Historical Castles and Mansions of Scotland (Perthshire and Monmouthshire)”, Alex Gardner, 1890.

3. Richard Aldington & Delano Ames, trans., Felix Guirand, ed., "Larousse Encylopedia of Mythology", Batchworth Press, 1959.

4. Brian Branston, "The Lost Gods of England", Thames & Hudson, 1957; Ralph Whitlock, “In Search of Lost Gods, a Guide to British Folklore”, Phaidon, Oxford, 1979; Robert Graves, "The White Goddess", Faber 1948.

5. George Cadenhead, “The Family of Cadenhead”, J.P. Edmond & Spark, Aberdeen, 1887.

6. William Ferguson, “Scotland’s Relations with England: a Survey to 1707”, John Donald Publishers Ltd., 1977.

7. Hew Scott, ed., “Fasti Ecclesiae Scotticonae”, Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh, 1926.

8. Information from “Surnames of Scotland”, photoprint from New York Public Library supplied by National Library of Scotland.

9. Gérard Serbanesco, "Histoire de l'Ordre des Templiers et les Croisades", Byblos, Paris, 1969.

10. Grant M. Waters, “Dictionary of British Artists Working 1900-1950”, 2 vols., Eastbourne Fine Art Publications, 1975, 1976.

11. (Anon), ‘Sculpture Work by the Late Albert M. Hodge’, The Builder, 8th February, 1918.

12. (Anon), ‘Mr. A.H. Hodge’, obituary, The Times, 28th January, 1918, p.8 col.6.

13. Marilyn Baker, Ph.D, Assistant Professor, Art History, School of Art, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, letter to the Glasgow Herald, 6th April, 1978.

14. ‘Stirling Burns Statue, Provost Bayne’s Gift’, The Stirling Observer, 25th September, 1914; ‘Provost Bayne’s Gift to Stirling, A Fine Statue of the National Bard’, Stirling Journal and Advertiser, 24th September, 1914.

15. Morris Lindsay, ‘Scotland Now’, The Scottish Field, November 1963.

16. F. and V. Hitching, “The Royal Air Force at Hunsdon 1941-1945”, The Hunsdon Local History and Preservation Society, 1990.

©DuncanLunan2013